Download our new brochure online!

Valle Stura

A wide valley corridor that descends from the innermost Western Alps to the Piedmontese plain and tickles the city of Cuneo. A heterogeneous environment where the breath of man delicately intertwines with an authentic and suggestive natural landscape. It is possible to immerse oneself thanks to a dense network of paths, roads and mule tracks that still smell of history and tradition. Suspended between the Maritime Alps and the Cottian Alps, Italy and France, the Stura di Demonte Valley flows into the Cuneo plateau through the Gesso and Stura River Park: a naturalistic lung of over four thousand hectares that extends over ten municipalities, preserving peculiarities of fauna and flora. From Cuneo to the Colle della Maddalena, for an environmental mixture that lends itself well to a simple trip out of town but is equally suitable for a multi-day immersion in sport, nature, history and quality food and wine.

History

The Stura Valley has been an important transit route between Piedmont and France since ancient times. It has been inhabited by man since the Neolithic. In this period, groups of shepherds settled in the middle of the valley. They used natural cavities as dwellings, pastures for their domestic animals and stone to make chipped and polished tools.

The Stura valley was conquered by the Romans in the Augustan era, after being inhabited in pre-Roman times by the Liguri Montani. The alpine territory of the Maritime Alps formed the province called Alpium Maritimarum, aggregated to the customs district of Quadragesima Galliarum. From the Argentera Pass, the boundary line of the province descended through the Stura Valley to its outlet at the ancient town of Pedona (today Borgo San Dalmazzo). Even then, the territory was already of great importance due to its passes that guaranteed easy transit to France.

From the 5th century onwards, the valley first suffered the barbarian invasions and then, in the 9th and 10th centuries, those of the Saracens. At that time the valley was part of the possessions of the Benedictine abbey of Pedona.

From the 11th century, more precise information began to emerge about the municipalities that made up the valley. We certainly know that in 998, this mountainous district was part of the fiefdom of the Bishop of Turin, under whose control it remained until around 1150. Throughout the 12th century the area was under the dominion of the Marquisate of Saluzzo, and in the 13th century it was subjected to the expansionist thrust of the municipality of Cuneo, linked to the Anjou: they took possession of the district from Aisone to the Maddalena hill, uniting it with Provence in 1259. Over the following centuries, the Savoy family tried several times to take over the district. In 1388, their dominion extended as far as the parish of Sambuco. In the meantime, with the annexation of Provence to the Kingdom of France, the rest of the valley came under the rule of the French crown.

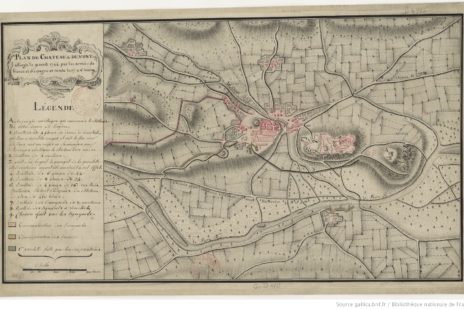

In 1588, the Savoy finally succeeded in taking possession of the entire valley. The last part of the territory to fall under Savoy rule was the one currently represented by the municipalities of Roccasparvera, Gaiola, Moiola and Demonte. Under Savoy rule, the Stura Valley witnessed numerous wars; the transit of troops during the War of the Austrian Succession and the Napoleonic campaigns were particularly significant. At the end of the 16th century, to contain a hypothetical enemy advance, Carlo Emanuele I of Savoy had the Fort of the Consolata built on the rocky terrace known as “il Podio”, next to the village of Demonte. The Fort was “modernized” in the following century and suffered a single siege in the summer of 1744, during the War of the Austian Succession. In the 17th century this border territory kept being witness of the passage of armies: in two consecutive years Vittorio Amedeo II of Savoy attacked the French Dauphine with an army of about 30 thousand men; the army commanded by the Marquis of Parella, in its advance, passed the village of Vinadio and encamped at Sambuco on 26th July 1692.

All the municipalities were forced to support the military contingent with continuous supplies of hay and provisions, and this led to the imposition of heavy taxes on the already miserable population. The following years were also characterized by continuous looting and devastation, which only ceased with the peace of Rijswijk on 20 September 1697. On 22 May 1708, enemy columns descended on the Stura Valley and clashed with a counter-offensive led by the Count of Thun in the summer. The battleground was Vinadio and in the clash, in addition to the soldiers, also civilians, women and children lost their lives. In 1744 the Gallo-Spanish army overwhelmed the resistance of the Piedmontese and Austrians and descended into the valley besieging the stronghold of Demonte. On the 9th August the invaders opened a trench and for nine days the fighting was continuous. The Galloispani soon found themselves facing the fortified city of Cuneo. On 15th September the Siege of Cuneo began and ended on 21st October 1944 with the retreat of the invaders.

In the 19th century, an imposing barrage was built at Vinadio, consisting of Fort Albertino located in the city and other forts on the surrounding heights. The construction was planned in 1830 but work, involving up to 4000 people, began only in 1834 and was completed in 1847. Despite an interruption of two years, between 1837 and 1839, a true masterpiece of engineering and military technology was achieved in just eleven years. Due to changed political and strategic needs, the fort was never used for military purposes. The imposing structure is still a historic monument that characterizes the valley and the western Alpine arc. Nowadays it has become a venue for shows, events, and exhibitions. During the 19th century the Stura Valley was still the scene of military crossings and border warfare, but as time went by it became more and more the destination of peaceful “invasions” by hikers, writers, scholars, artists, lovers of science and travel. By the eighteenth century the “touristes” came to the Alps for the Grand Tour, the long journey of the rich young men of the European aristocracy who wanted to broaden their knowledge of geography, anthropology, politics, and art. The Savoy royal family was a very important presence in the Stura valley: part of the royal hunting reserve, which covered the Gesso Valley, also extended to some of the municipalities in the Stura Valley, such as Aisone, Vinadio, Demonte, Sambuco and Pietraporzio.

During the Fascist period, two defensive lines were built in the valley: one at Barricate, on the border between the municipalities of Argentera and Pietraporzio, the other on the narrowing of the valley above Moiola. These buildings were never used for the military purposes for which they were intended. On 10 June 1940, when Mussolini declared war on France, the Stura valley found itself in the first line of fire of the conflict. The so-called ‘Maddalena line’ was one of the most important lines of penetration planned by the offensive. From September 1943, the Stura valley became the cradle of the Italian Resistance and the national liberation struggle. On 12 September 1943, the first group of partisans was formed near Madonna del Colletto. Duccio Galimberti, Dante Livio Bianco, Arturo Felici, Dino Giacosa, Ettore Rosa, Leandro Scamuzzi, Edoardo Soria, Ildebrando Vivanti and Ezio Aceto were part of this group. On 20 September 1943, the partisans of Madonna del Colletto moved to borgata Paraloup, in the territory of Rittana, which soon became the center of important partisan operations. On 11 February, Nuto Revelli came to Paraloup. From that moment until the Liberation in April 1945, the Stura valley was in a continuous state of war and the civilian population of the valley took on a fundamental, courageous, and heroic role. This role of the local population was decisive to the conquest of freedom and peace that sealed the end of the Second World War.

In the sixties and seventies, the Stura Valley, like other mountain territories, experienced the phenomenon of depopulation: the mountains, which for centuries had guaranteed the inhabitants an economy of self-sustenance and dignity, were abandoned. Many families of mountain dwellers were dispersed towards various migration destinations. Only a few villages on the valley floor, such as Demonte and Borgo San Dalmazzo, were able to act as a barrier to the abandonment of the valley, thanks to the establishment of some small and medium-sized production activities. However, while the highlanders abandoned their homes and villages, the territory saw an increase in the presence of tourists. The last decades have seen an upturn in the sectors which have always characterized the mountain economy: agriculture, livestock breeding and sheep farming. At the same time, interesting museums have been developed to promote and preserve ancient traditions, such as the multimedia center Montagna in Movimento in Vinadio and the Eco-museum of Shepherding in Pontebernardo.